Our research director, Natalie Novick was invited by the Global Entrepreneurship Network to present the results of her research to global decision makers on stage at the Startup Nations Summit in Estonia. Read below the full excerpt of her talk.

Talk prepared for the 2017 Startup Nations Summit – Tallinn, Estonia

By Natalie Novick. Â Â

The goal of my talk today, is to show that anyone, anywhere—from wherever you sit and whatever resource you have—can work to improve their startup ecosystem. If you are a bureaucrat, a community member, a founder, or just someone interested in startups—there is a role for everyone, and everyone can do something here.Â

There are many that have spoken about developing strong tech ecosystems, about what they need, about what you need to put into them, about what laws you need to change, what types of talent you need to import, and what kind of money that has to be raised to make it happen.

Often those we listen to who have written previously about startup ecosystems tend to be investors, or those involved in economic development. Ecosystems are vitally important to them because they are looking to get a return from the startup ecosystem. They know that a vibrant startup ecosystem can help sustain and propel profit rich companies. I come to this investigation from another angle, as a sociologist. My research is on startup ecosystems, what they are, who they are comprised of, and what they mean to people. Sociology involves the study of the social bonds people form with one another. Further, it involves the study of how communities develop, the social forces that govern them, and how the environment can shape their activity. This provides a unique perspective to approach the topic of startup ecosystems, as everyone here will know well, that more happens inside them than just business.

It is from this vantage point that I find vibrant startup ecosystems help support much more than economic development—they can help project positive messages about technology and business practice to the wider community, dissolve entrenched inequalities and discriminations in the workplace, and help bring people together in a positive way. These positive externalities of the startup ecosystem are outcomes that communities across the globe are looking to promote more widely. But how can this be achieved?

Don’t accept compromised data as truth

When we want to first evaluate our startup ecosystem, the first step usually is to measure it. Measurement is a key step to conduct when you are looking to improve or build on something.  I have a background as a data scientist and a survey methodologist, and when I talk with academic audiences, we utilize lots of graphs, numbers, data. Whether you are in academia, government, or business, analytics are important as it shows us what we have, what we don’t have, what we need to improve on. Data gives us a baseline for what we can do and where we can see where we are going and what we can do better. Except when it doesn’t.

Data is only as good as its inputs. What we see happening, is that even in the age where we have more data than ever before, the types of data we have available is incomplete. Measures are constructed based on data availability, and not informed by theory. The measures that go into many of these startup indexes utilize whatever data availability we have, at whatever level of analysis we have. In addition, rarely does anyone question the data—people accept data that comes from sources that are unknown to them, from questionable sources or from for-profit providers.

Leaning on indices and metrics like these can lead to rash conclusions, and do not allow us to see what is going on within the lines. The data we utilize can mask certain phenomena that is unmeasured under the surface.

The second problem with available data, is the methodology. Methodology involves the construction of how these indices, and how values are put together. Much of the time, they are not theoretically motivated. Partly because, this is a rapidly changing field, and there remains much theory development to be done, but also partly due to their orientation. Often these indices are built by private entities, specialists, and corporations for self-interest. Municipalities pay for their inclusion for fear of being “left out†of a global conversation. And– the construction of these indices seems to imply—that every startup ecosystem needs to be measured the same way, and evaluated according to the same inputs and outputs.

In Academia, we have a pretty healthy conversation about the limitations of data and the problems of methodology. But outside, this does not happen to the same extent. Oftentimes we accept the existing indices and metrics from companies that utilize sources that are untested, where the methodology is unquestioned, utilizing sources they do not understand nor question—because they don’t have anything better.

Developing your own metrics

My background is in quantitative analysis and survey methodology. I am a statistical person. But for the last 18 months, I have been engaged in an ethnography of startup ecosystems—approaching the startup scene as an anthropologist — because many of the key elements of a startup ecosystem are not easily quantified. These elements, comprise key facets of our startup ecosystems that indicate how well they sustain the communities they serve. But they don’t often show up on many of these rankings because they are not easy to measure. Because they are not easily measurable, it does not mean that they cannot be measured. Once you have engaged in the qualitative discovery process, you will be able to apply metrics to the features of your ecosystem that you find important.Â

In my research, I have identified a number of facets that are sociologically interesting. I tend to spend several months in an ecosystem discovering them—but you, as ecosystem builders, and community members, you are equipped to do this work.

By discovering the key qualitative aspects of your startup ecosystem, by truly understanding them, you can learn to measure them and utilize them in your efforts to build and improve your ecosystem for everyone.

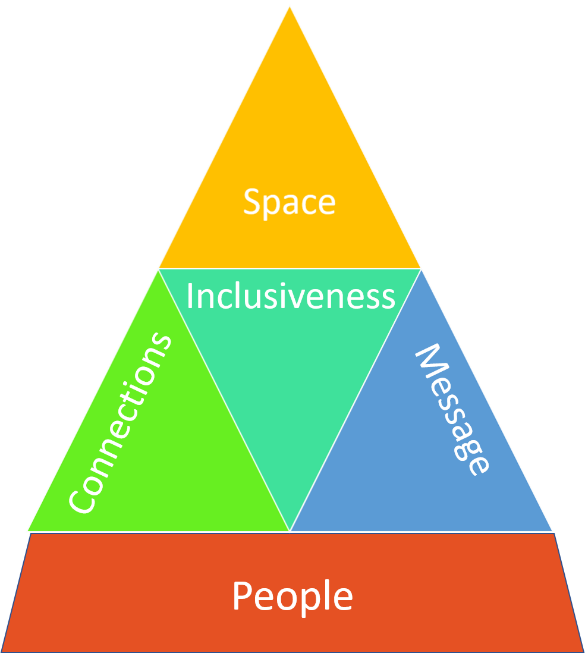

The Startup Ecosystem Food Pyramid

I have arranged some of the key qualitative components that I have found to be particularly important towards sustaining the startup ecosystems I have studied in the above, Startup Ecosystem Food Pyramid. These components are not easily quantifiable, and often do not appear in traditional metrics of startup ecosystems. Each of these constitutes an important component for community building. Don’t necessarily look at the size of the segments here—these can differ based on your ecosystem’s unique needs—or the orientation, particularly. It is important to keep in mind that these components are not exhaustive—but they identify some of the most important characteristics about your ecosystem—that you as community members and ecosystem builders—need to evaluate.

Space

Space is the protein of the startup ecosystem, and is the element that helps startup ecosystems to grow strong. The early story of Silicon Valley is one that prized the role of garages as workshops that led to the creation of some of the world’s most laudable companies—HP, Apple, Google, these were all built in someone’s garage. Garages are not so numerous and accessible to everyone around the world, but if you want to build anything, a product, a company, a community, you will need to have a workshop. What is unique about a garage is that it is a place to work, a place to get your hands dirty, and a place that is really accessible to a lot of people, you don’t need the right suit to enter. Its not a particularly clean place either. Keep that in mind as you evaluate the startup spaces in your ecosystem.

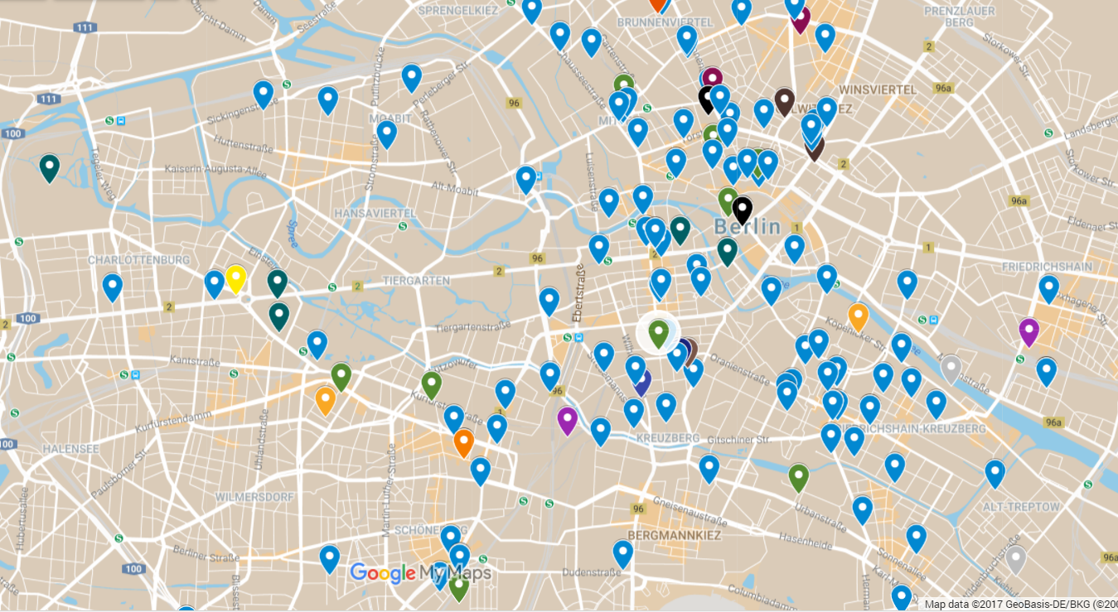

The above is a sample of a map I made of 161 of Berlin’s spaces I visited during 6 months in the startup ecosystem there. They are co-working spaces, assembly areas, special congregation rooms in corporate environments, to coffee houses and convention areas. In Berlin, these spaces and rooms to congregate— hosted about 1200 tech events last year, depending on how you measure the data.

The above is a sample of a map I made of 161 of Berlin’s spaces I visited during 6 months in the startup ecosystem there. They are co-working spaces, assembly areas, special congregation rooms in corporate environments, to coffee houses and convention areas. In Berlin, these spaces and rooms to congregate— hosted about 1200 tech events last year, depending on how you measure the data.

Space is what allows entrepreneurs, and startuppers to engage in the community practices of entrepreneurship that have become key features of the entrepreneurial process. These are places to learn, to share, and to build. But not all of these spaces are created equally. It is not simply counting the number of these spaces—you need to examine how they work. If you want to evaluate them, take some time to visit them. Sit in the back and observe how they are being used. Who is using the spaces, and what are the spaces being used for? Are these more technical talks, or more about key aspects of the company ideation process? Are they positioned more for the startup stage, or the scale up stage? Are there barriers to participating? Are the events well attended? Are people participating, asking questions? Or sitting quietly? What does the life look like in these spaces? Do you get a comfortable feeling, or one that ls less comfortable? Does it seem that people have adequate room to grow, collaborate, and exchange with one another? Are there barriers to participation? Does it feel like a space someone with little technical or practical startup expertise would feel comfortable entering?

The type, amount, quality, and density of the spaces available will significantly impact the type of exchange that happens in them. Room that is freely available, will be a haven for those to work. Spaces that are offered by sponsors or by the community will encourage those who are inclined to host their own events, and build their own communities on top of the startup ecosystem there. Social platforms make it easy to connect likeminded people, but having a venue to meet offline is an important community asset. What is the consistency of the events? Is there a lot of training going on? Is every night a pitch night? Or are people trading skills and building things together? What interaction is happening? Use these questions to orient the discovery process. Once you begin to answer these questions, you can begin to formulate your own questions, and begin to attach metrics to them. You can compare for example, the amount of spaces that are open to hosting technical events, compared to those that are for ideation, and business strategy. You can evaluate the amount of people that are coming into these spaces, and the types of interaction they are having. As you begin to develop metrics that are appropriate for your community, you can compare how these change over time, or with the treatment of certain initiatives. Utilize your own understanding of your community’s spaces to identify your unique needs and orient your activities going forward.

Inclusiveness

An inclusive ecosystem is one that is open to everyone, and presents itself that way. It is a place for people from all levels of society, with an entrepreneurial mindset to feel welcome and where they can come together. The benefits of cultivating a diverse ecosystem are well documented. Diversity insulates from groupthink, it makes teams more innovative, it makes products more robust and testable in more markets. More diverse ecosystems can harness the variety of skills brought together from various perspectives. But we know, that not everyone has an equal opportunity to participate. Black software engineers make less than whites do, and minority candidates are less likely to be hired, for not fitting into the culture. Further, the technical tools and skills that help us to build and create in this digital economy are not available to everyone.

A great startup ecosystem is a place where everyone can feel welcome. And no one is excluded. There are a number of great initiatives working to tip the balance here, and the visibility of organizations like these (Opentech School, Czechitas, Refugees on Rails, etc), helps to send a message about your ecosystem’s approach to the world.

How do you know if you have an inclusive ecosystem? Take the time to ask people. Attend events, and observe. Are there older people participating? Young people? Mostly men? International/non-native people? Listen. It is not about the quantitative metrics of how many female founded companies you have, or how many minority candidates that are hired. Inclusivity is one of the hardest things to promote—but if you have good information, that you constantly update—you can begin to understand where the unique challenges are.

When examining your ecosystem’s events, consider aspects such as language, to see how language can include or exclude people. English language use is important—it gives the opportunity to communicate and express oneself across multiple geographies, but it has pros and cons. For example, English language skills are one of the most important aspects of success for startup founders when they are raising money, and for engineers and developers for getting hired—but an ecosystem exclusively in English, when this is not the native language, can make barriers for some.

Similarly, investigate how well your ecosystem integrates non-native people. International students and founders are important aspects of a startup ecosystem—indeed a large portion of founders in Silicon Valley come from outside the US or were former international students. But this progression from university to business only works if those international students can feel at home in the community. This is not always the case. Look for possible barriers within your community if this is not the case, and identify how bridges can be built to make this group feel more included.Â

Connections

Just as companies are born global today—similarly, the ecosystem for entrepreneurship is a truly global one. This is the larger story of the Startup Nations Summit, the event that has brought us all together here. Your community must be participating in this global conversation—and as you are all here, that’s a great start! Building meaningful connections across cities, across borders and across a region—is the best way to increase the impact of your ecosystem overnight. Work to build meaningful connections by finding a shared point of exchange value. For instance, is there a shared vertical that you can promote? Is there an exceptionally good train or plane connection to this city? You as ecosystem builders need to be in conversation with startup ecosystems that are outside your specific sphere of influence. Work hard at promoting these connections—and you will have the opportunity to make something really special.

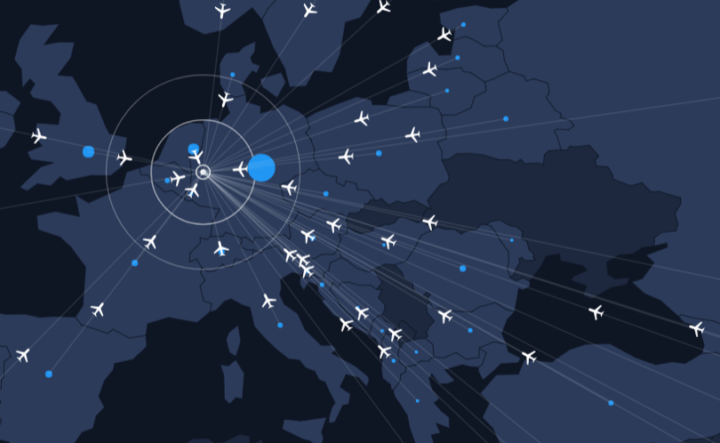

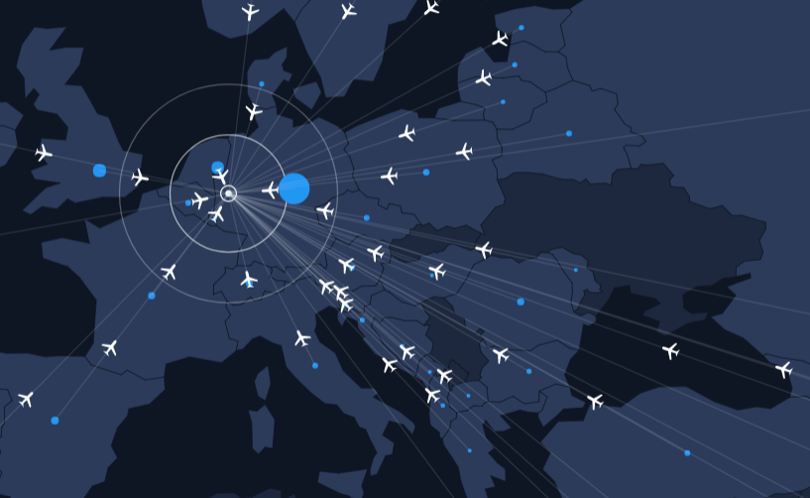

This above is part of a map we did at Startup Heatmap Europe for a tech event a little while ago. It depicts the origins of attendees that are coming to attend this specific event. In your ecosystems you may have similar ones. How are you harnessing and utilizing these people? Are these single serving connections? Or are they something more? Interestingly, when we asked many of these international participants at the event about their impressions of the startup ecosystem in this city, they had a limited understanding. The visitors knew the event, but that was it. This is a single serving connection. It showcased an area where the ecosystem could do much more to capitalize on the high volume of international visitors, to create more impact.

This above is part of a map we did at Startup Heatmap Europe for a tech event a little while ago. It depicts the origins of attendees that are coming to attend this specific event. In your ecosystems you may have similar ones. How are you harnessing and utilizing these people? Are these single serving connections? Or are they something more? Interestingly, when we asked many of these international participants at the event about their impressions of the startup ecosystem in this city, they had a limited understanding. The visitors knew the event, but that was it. This is a single serving connection. It showcased an area where the ecosystem could do much more to capitalize on the high volume of international visitors, to create more impact.

Connections across ecosystems come from many things—investments, hometowns, events, talent to suppliers. You can build these connections is by utilizing your existing ones. You will begin to build outwards. Ask questions of your visitors, and look hard at the data you have available to you to see how these connections are being made. Do you have a certain vertical that you are investing in heavily? A special talent, or cluster? You can work to reach out to places that also share these strengths. Are there other connections that might make sense? Do you have a sister city? Or a place that has a great nearby train or plane connection? You can start there. Identify how people connect to your ecosystem.

Finally, you should question how are you utilizing your diaspora. A startup ecosystem, cannot be everything to everyone all of the time. Entrepreneurs are transnational people, they will by their very nature be likely crossing borders, moving cities, maybe many times in their lifetimes. Don’t punish them for going—try to find a way that they can still remain connected to you. They can be your best ambassadors abroad. Look at the incredible impact of the French Tech project, or simply how using a hashtag like the #estonianmafia can unite people together. Similarly—a great Greek startup cluster exists in London, and it has become a magnet for funding, and for newcomer Greek entrepreneurs to the city to find a foothold. Utilize your diaspora and work with them to showcase your strengths, and give them reason to return, to share knowledge and give back.

Message

The last qualitative aspect I am going to talk about today is message. Your message, is how you communicate yourself to the world, and how the world, can see what you have to offer. Your message is one that is descriptive, accurate and continually updated. Your message is one that your community can align under. What is the first association people have with your startup ecosystem?

One way to align your message is using a “Flagâ€. This concept, of a ecosystem hashtag was designed by Tyler Crowley, who started the Stockholm Tech meetup—now today Europe’s largest monthly tech events. A big part of the success of this meetup came from its aligned messaging. If everyone in your ecosystem is able to combine their message under multiple platforms, it can be a valuable tool. Another way to take control of your message is through a platform—and here, no one does it like Estonia. The startup Estonia website, tells you everything you need to know about Estonian startup ecosystem, the places, destinations, etc. Take control of your message,

But to know your message—you need to understand how it is perceived. At the Startup Heatmap, we have done a lot of work with founders, asking them about their top destinations to startup in Europe. And what we find, is that founders sometimes, do not know a lot of information. Often, their associations are not detailed. They don’t know where to get the information, and sometimes their associations are just plain wrong. I ask people some for their first associations of the startup ecosystem in the places I am researching—and sometimes the replies are, “its smallâ€, “its coldâ€. Pressing them further, they cannot name the top companies there, the top companies—they do not know that story. Founders are primarily concerned with the development of their companies. They do not have a lot of time to fish for information. If you want to attract them to your ecosystem—your message, of the value you can offer them, must be as clear and efficient as possible.

Ecosystem builders need to take the lead, and craft the story you want to tell. Make sure it is representative—and one that the ecosystem is on board with. You cannot just grab a hashtag, and run with it and expect people to jump on board. Similarly, with branding efforts—a city, that will remain nameless—is utilizing a branding campaign—that when you ask entrepreneurs about it, they find it embarrassing. They will not get on board. Bring them into the conversation. Â

People are the foundation of all startup ecosystems

Ultimately, entrepreneurial ecosystems are about people. Startuppers are among the most misunderstood people out there. They are misunderstood by their families, their friends, the industry and also by civil society. The founders we talk to—they are at times have the perception that their local government is unfairly credit claiming from their accomplishments, and worse—their municipalities and governments are openly hostile to them. Localities, they are frustrated when startuppers do not engage with their initiatives. Miscommunication goes both ways.

A great startup ecosystem depends on people to sustain it. Communities are built on trust, and understanding. Foster an environment where both of these qualities thrive. For those of you on the community side—take the time to get to know your startuppers. Find out what motivates them, what their pain points are, why they are entrepreneurs, what their kids names are. The more you get to know your startup scene—the more you begin to uncover what your ecosystem’s entrepreneurial identity looks like. The entrepreneurial mindset—is one of the most important qualities of an entrepreneur. But what does this look like in your ecosystem? Are you finding your entrepreneurs risk adverse, and scared to share with one another? Is entrepreneurship an act of desperation, found out of a loss of all other alternatives? Or is entrepreneurship bound out of a daring to try, facilitated by a welcome, and supportive environment?

By getting to know your entrepreneurs and their teams, you, as community builders will learn what they need. You might find that they are risk adverse, or find that they are vulnerable, being taken advantage by corporate VCs. Based on your discovery process, you will know what you will need to invest in your ecosystem. Make a commitment to say that your door is open to hear from them. Do not always expect them to come to you—you need to demonstrate the effort that you are open to hearing from them, and you value what they have to say.

This conversation is not one driven by one partner. Startuppers—know that the city, and the government and your community cannot read your mind. You need to work to communicate your needs better, and consider their perspective. At the end of the day—what is good for you, is good for them. You are on the same team. Use this common ground as a place to build a meaningful relationship.

Knowing your qualitative metrics means knowing what you have to offer

If you only know the quantitative side of your startup ecosystem—you are missing the entire story. And you will be unprepared to make it grow. Investing in building up these qualitative insights is hard work. I heard from a global intergovernmental organization (names withheld to protect the guilty) last week and in their analysis of startup ecosystems—they said they spend one week evaluating the culture in each city. That’s not enough time. You cannot expect to get the right insights if you only utilize those from outside experts, or talk to those who are the most visible in your ecosystem. You need to speak with a wide variety of people that are involved, and more importantly, as community builders, you need to participate in it yourselves.

Once you begin to uncover these qualitative insights, you can work to attach quantitative metrics to these qualitative insights. Continue to evaluate and measure how things change. It is only by devoting this attention, you will see where you are going and what you need.

As you begin to uncover your value, and build upon your strengths as an ecosystem, its up to you to share it more widely. You cannot depend solely on media to tell your story for you. Be the architect of your own story, and work hard to communicate your value. You need to share these understandings, share what is unique and special about your ecosystem. Right now, this is not happening nearly enough.

The benefit of an authentic message that communicates your value is immeasurable. Greater visibility about your ecosystem can work to attract those who want to be a part of the things they see happening there. Greater visibility means your startups are more recognizable, and international partners can put greater trust in them, because they can easily find out more about their story. Excellent communication indicates to investors, corporates, and other ecosystems that you are participating in a similar global conversation. Don’t count out your qualitative insights in a quantitative world. Every ecosystem has something to offer. It is up to you to identify and evaluate these core qualities, and work to improve and amplify them.Â